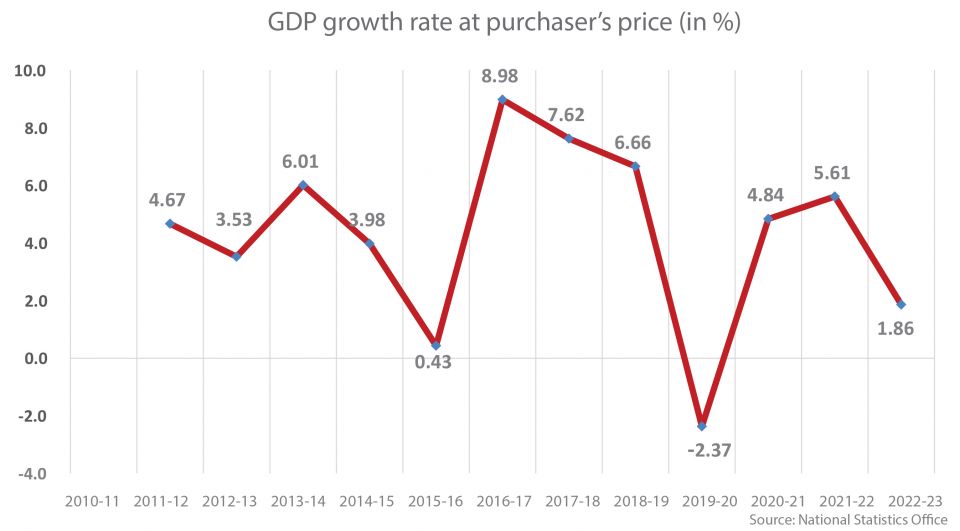

The latest estimate is 1.86 percent, down from 4 percent during the first half and 8 percent at the start of the fiscal year.

Nepal has been progressively downgrading its growth projection as unsound policy and political instability take their toll on the economy.

At the start of the fiscal year, the government had pompously declared that the economy would grow by an astounding 8 percent. But reality set in as the economy floundered, and the figure was halved to 4 percent during the mid-term review of the budget.

The new projection was still too high. On Tuesday, the National Statistics Office said the economy would not grow by more than 1.86 percent.

“That’s the true picture of the economy,” the National Statistics Office told the press.

Formerly known as the Central Bureau of Statistics, the official number cruncher said that its prediction, for the first time, falls far below the estimates of multilateral funding agencies like the Asian Development Bank, World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

“We have presented what our findings have shown. Our results show that the country’s economic situation is not good. We urge the press to disseminate this information to the people and all three tiers of government,” said Ram Prasad Thapaliya, chief statistician at the National Statistics Office.

Nepal’s economy, which rebounded strongly after Covid, has been marred by political instability and haphazard decisions to gain short-term benefits, economists say.

“But all indicators are not bad. The economy may improve in the coming days,” said Thapaliya.

Computed on the basis of this growth rate, Nepal's gross domestic product is estimated to reach Rs5.38 trillion at the end of the fiscal year in mid-July.

Experts had flagged the emerging crisis months ago.

Economist Chandan Sapkota said that the tight monetary policy to maintain external sector balance, especially to narrow the current account deficit and increase foreign exchange reserves, and lower public spending had dampened aggregate demand.

That led to lower-than-expected real GDP growth, which at 1.9 percent is the lowest since the fiscal year 2015-16, the year Nepal was hit by the earthquakes, except for the contraction in 2019-20 caused by the Covid pandemic.

Ishwari Prasad Bhandari, director of the National Account Section of the statistics office, said that the 1.86 percent growth estimate is based on actual data for nine months and forecasts for the next three months.

"The remaining three months' estimates are based on the assumption that everything will be normal. If everything remains the same, the performance of all economic sectors will be the same as in a normal year.”

Bhandari said that the agriculture sector, which contributes 24.12 percent to the country’s economy, was projected to grow by 2.73 percent this fiscal year.

Nepali farmers are expected to harvest 5.48 million tonnes of paddy this fiscal year, which is 7 percent more than last year. Paddy output grew despite a severe shortage of chemical fertilisers.

“But the winter drought caused winter crop yields to fall below expectations. The production of meat and eggs did not grow either,” said Bhandari.

Illegal crusher factories were temporarily shut down in January 2023 which led to a shortage of construction materials such as sand and aggregates. Post File Photo

Mining activities too were hit. Illegal crusher factories were temporarily shut down in January 2023 which led to a shortage of construction materials such as sand and aggregates. This slowed down development projects.

The construction sector, which contributes 5.52 percent to the GDP, dropped 2.62 percent. Last fiscal year, the construction sector had grown by 7 percent.

The retail and wholesale sector, which accounts for 15.39 percent of the GDP, plunged 2.96 percent, the statistical office said. In the last fiscal year, the retail and wholesale sector had expanded by 7.46 percent.

But the economy started to really suffer when the government decided to restrict imports.

Last April, alarmed by the fast pace at which Nepal's foreign currency reserve was diminishing, the government imposed import restrictions besides ordering importers to maintain a 100 percent margin amount to open a letter of credit. The ban was lifted in December last year.

“The restriction on imports hit the government’s revenue collection. It failed to pay thousands of contractors, and they, in turn, failed to pay their workers,” said Bhandari.

Economist Keshav Acharya told the Post in a recent interview that the prolonged foreign exchange controls by the government were the reason for the current economic slump.

“After a few months of import restrictions, the results became visible. Our country is now an import-driven economy, and restructuring imports means shooting oneself in the foot.”

The market, as a result, went into the doldrums. Stores are seeing a slowdown in discretionary spending by consumers, primarily because of inflationary pressures, reflecting how a slowing economy has dampened the market mood.

A credit crunch, real estate slowdown, tumbling stock market and rising unemployment have rattled the economy even as a new government was formed.

Nepalis are not buying cars, furniture, gold and clothes. Stores in Kathmandu’s major markets like New Road, Mahabauddha and Durbarmarg have launched sales offers, but buyers are still not showing up.

People are spending less at restaurants and purchasing less goods for their homes. They are cutting their budgets almost everywhere.

“Political instability has added to the economic woes,” said Acharya. “The government was least bothered to address the problems. The private sector, too, did not spend.”

Moreover, high inflation eroded the purchasing capacity of the people.

The agriculture sector, which contributes 24.12 percent to the country’s economy, was projected to grow by 2.73 percent this fiscal year. Post File Photo

Foreign direct investment too dropped to a new low. According to Nepal Rastra Bank, Nepal received foreign direct investment totalling Rs1.17 billion in the first eight months of the current fiscal year, a steep plunge from the Rs16.30 billion it received in the same period of the last fiscal year.

“This is because of political instability,” said economist Acharya.

When there was no demand, the manufacturing sector too began to stagnate. The output of the manufacturing sector, which contributes 5.32 percent to the GDP, plunged by 2.04 percent. The manufacturing sector had grown by 6.74 percent in the last fiscal year.

“In the manufacturing sector, the production of vegetable oil, ghee and iron was negative,” said Bhandari.

Manufacturing, construction and retail and wholesale trade—which together account for about 28 percent of GDP—contracted.

“This indicates not only lower industrial capacity utilisation due to higher cost of production including issues with electricity supply, inflation and input costs; but also direct and indirect policy restrictions on real estate transactions and deliberate measures to discourage imports,” said Sapkota.

While public and private investments contracted by 20.2 percent and 7.6 percent respectively, consumption expenditure slowed down to 3.7 percent.

“Moreover, export growth moderated, and the restrictive import regime, along with a tight monetary policy, strangled total imports,” Sapkota said.

“Consequently, the external sector, and to some extent, the financial sector indicators have improved; but this has come at the cost of a slowdown in imports and overall economic activities.”

He said that lower-than-expected capital spending and recurrent spending rationalisation, partly due to lower revenue mobilisation, also hurt economic activities and banking sector liquidity.

Electricity production, which expanded at the rate of 53.35 percent in the last fiscal year, is estimated to grow by a meagre 19.36 percent in this fiscal year. The import of industrial raw materials dropped by 13 percent, said Bhandari.

Due to the import restrictions, vehicle imports, the major source of government revenue, were also hit.

The National Statistics Office has estimated that the per capita gross national income or per capita income may rise to $1,410 this year from $1,381 in the last fiscal year.

The per capita GDP may reach $1,399 in the current fiscal year, from $1,372 in the last fiscal year. The per capita income means the average annual income of a person.

According to the report, the final consumption expenditure or money spent by Nepalis on consumption will reach Rs5.03 trillion, which is 93.59 percent of the total GDP.

“This means people are saving less or on average a person saves 6.4 percent of their income, which is so far not good,” said Bhandari.

The statistics office said that the country’s resource gap is 4 percent of the total GDP.

“With the lifting of policy restrictions on imports, the gradual lowering of interest rates, decreasing inputs costs including fuel, loosening of real estate and housing restrictions, and a positive outlook for tourism and remittance inflows, economic activities will pick up pace next year,” said Sapkota.

“Improving domestic resource mobilisation and the budget execution rate, and taking decisive policy reforms to boost private sector confidence will be key,” he said.