Despite lingering reservations among electorates in Bhutan and India regarding Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs), officials from both countries say that these machines are secure, reliable, and efficient.

Senior Deputy Election Commissioner of India, Nitesh Kumar, explained that EVMs are equipped with advanced security features designed to prevent errors and tampering, ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the voting process. “The machine is resilient against hacking and manipulation since it lacks outside connectivity with technical devices like Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and radio frequency transmission,” Nitesh Kumar said.

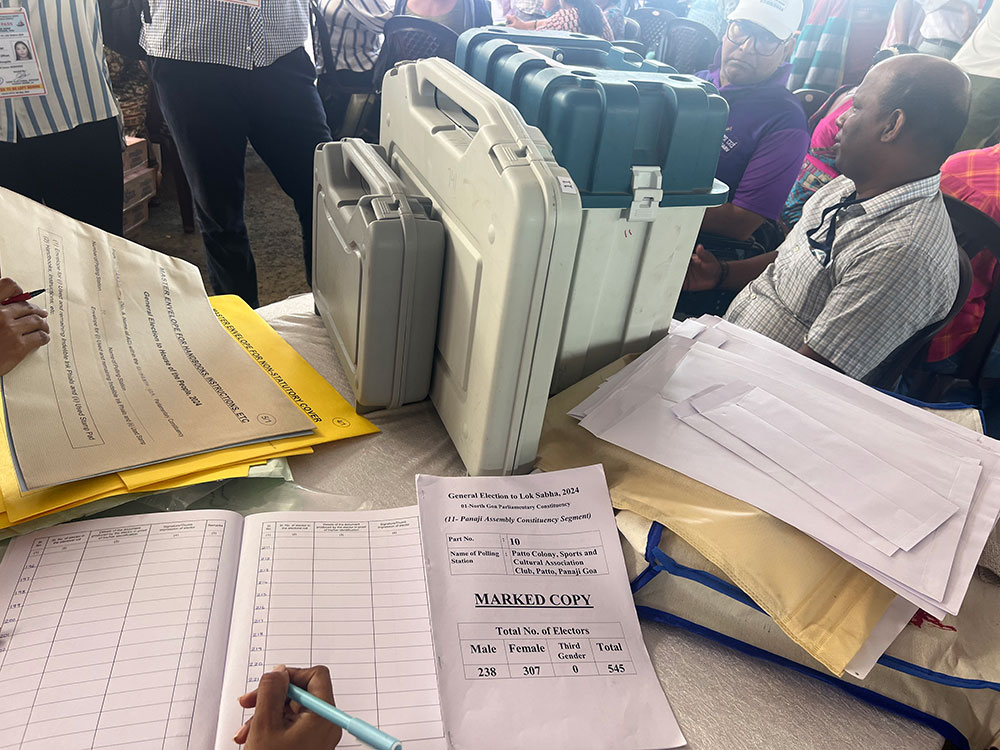

Kumar’s briefing was part of a week-long international election visitors programme for the ongoing 18th general elections of the Lok Sabha, organised by the Election Commission of India (ECI). Over 70 delegates from 23 countries, including 15 Bhutanese journalists and two senior officials from the Election Commission of Bhutan (ECB), witnessed the third phase of voting in 93 constituencies spread across 11 states and Union Territories.

Manufacturing and safeguards

EVMs are manufactured indigenously by Bharat Electronic Limited (BEL) in Bangalore and the Electronics Corporation of India (ECIL) in Hyderabad. These machines feature unauthorized access detection modules. “If someone attempts to physically tamper with the machines, the UDM module will automatically switch to factory mode, rendering the machine inoperable until it is sent back to the factory,” Nitesh Kumar said.

The ECI first used EVMs in the 1982 bye-election for the Paravur Assembly Constituency in Kerala. Nitesh Kumar added that the transition from paper ballots addressed logistical challenges and minimized vote counting delays, ensuring a smoother and more expedient electoral process.

With support from the Supreme Court of India and amended laws, the ECI has increasingly replaced ballot boxes with EVMs since 1998. “The EVMs have been used 100 percent in all elections since 2000,” he said, adding that the ECI had conducted four national elections and 148 state legislative elections, with 3.5 billion votes cast on EVMs to date.

The Supreme Court of India has consistently upheld the use of EVMs, dismissing public interest litigations that challenged their integrity. Ahead of the 18th Lok Sabha elections, the Supreme Court rejected calls to return to paper ballots, affirming that EVMs provide accurate results unless compromised by human intervention.

To enhance trust in the electoral process, Nitesh Kumar said that EVMs have recently been integrated with the Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) systemby the ECI. VVPAT provides voters with a physical confirmation of their vote by printing a slip that displays the candidate’s serial number and symbol for verification.

Public concerns

Despite these initiatives, some voters in India remain skeptical about EVMs. A businessman in Goa expressed concerns about potential hacking or manipulation, preferring the traditional paper ballot system.

In Bhutan, where imported EVMs from India have been used since 2008 for both parliamentary and local government elections, similar doubts persist. ECB Director Phub Dorji acknowledged that despite the accuracy, reliability, efficiency, and transparency of EVMs, some voters still harbor doubts.

A voter from Samdrupjongkhar expressed his concerns about the possibility of programming EVMs to favor specific political parties. Another voter from Thimphu suggested using National Digital Identity (NDI) and thumb impressions for authentication, arguing that digital methods could enhance security. “Even for postal ballots, every voter should send in their thumb impression,” he said.

However, some individuals express strong trust in EVMs. A political candidate who contested in recent elections highlighted the rigorous testing, cleaning, and sealing procedures that EVMs undergo. He expressed confidence in the machines’ reliability, backed by endorsements from the Election Commission and the Supreme Court of India. “If there was a possibility of manipulating the machines, why would we give so much emphasis on postal ballots?” he questioned.

An elected member from Bhutan noted that, despite public doubts, there is no evidence to suggest that EVMs can be tampered with. “Here in Bhutan, we have no evidence to prove that EVMs can be tampered with although people have some doubts,” he said.

Meanwhile, as India proceeds with its ongoing general elections, the fifth phase of voting is scheduled for May 20 in six states and two union territories. This election, which began on April 19, is the world’s largest democratic exercise, with 977 million eligible voters in 1.05 million polling stations manned by 15 million polling staff including security personnel. The results will be counted on June 4.