The Supreme Court Wednesday said “it will be a little extreme to suggest that material resources with the community will only mean resources which do hot have their origin in the private property of an individual”.

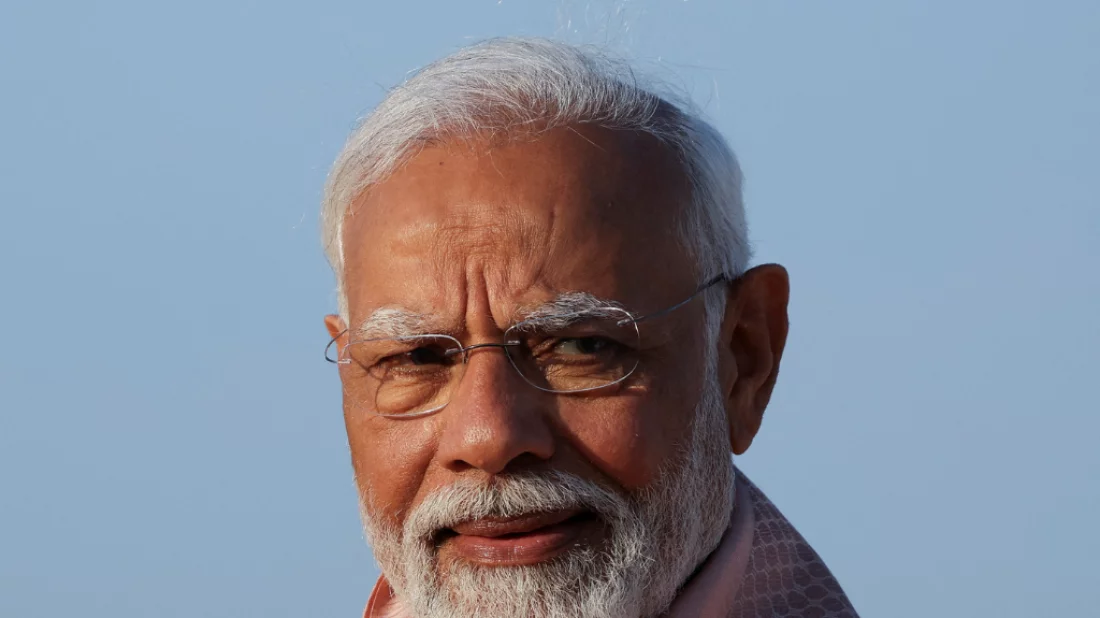

The remarks came from Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud who is presiding over a nine-judge Constitution bench that is answering a reference to it on the question whether the phrase “material resources of the community” in Article 39(b) of the Constitution covers what is privately owned. The bench also comprises Justices Hrishikesh Roy, B V Nagarathna, Sudhanshu Dhulia, J B Pardiwala, Manoj Misra, Rajesh Bindal, Satish Chandra Sharma, and Augustine George Masih.

Explaining his stand, the CJI said “why it would be dangerous to take that view? Take for example mines, forests or private forests. For us to say the moment a forest is a private forest, 39(b) will not apply and therefore its hands off would be extremely dangerous a proposition”. He added that it would all “depend upon context”.

Pointing out that the constitution was intended to bring about a social transformation, he said “so we must put ourselves back in the 1950s when the Constitution was made…You can’t say that 39(b) has no application once the property is privately held property”.

“Because the societal demands, the need for redistribution considering the societal perspective. So it may be airwaves, it may be water, it may be forests, it may be mines. In some areas probably the dividing lines become very clear. Just taking somebody’s flat…”

The CJI added, “but you must understand that 39 (b) has been drafted in a certain constitutional ethos, that the Constitution was intended to bring about a social transformation. Therefore we shouldn’t go as far as to say that the moment private property is private property, 39 (b) and (c) will have no application”.

Article 39(b) in the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) says that “the State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good”. Article 39(c) states that “the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment”.

The reference to the nine-judges had arisen in the context of a 1978 judgement in ‘State of Karnataka vs Ranganatha Reddy and Another’ wherein Justice V R Krishna Iyer said that material resources of the community would include both natural and man-made, publicly and privately owned resources.

Elaborating on this, the CJI said the “philosophical approach of Justice Krishna Iyer is this: If you look at the purely capitalist concept of property, it attributes a sense of exclusiveness to property… The socialist concept of property is the mirror image which attributes to property a notion of commonality. Nothing is exclusive to the individual. All property is common to the community. that’s the extreme socialist view”.

He said the Justice Krishna Iyer ruling deals with two aspects when they deal with 39(b) — the origin and the beneficiary. “The argument before the bench in Ranganath Reddy was that the origin must be in the community for 39 (b) and (c) to apply. If something does not originate in the community, then 39(b) can never apply.

Second argument was that distribution postulates that you distribute it to individuals. If you are not distributing it to individuals, then 39(b) will not apply. They deal with both these arguments at the philosophical level by saying that even if something that does not originate in the community, if it is a property of Nature, which has a bearing on the community, 39b is capable of application”.

The CJI also said it will be better if the 9-judge bench look into the question whether Article 31(c) continues to exist despite the ruling in the landmark ‘Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala’ case.

The hearing will resume on Thursday.