Government officials allege that more than 50,000 people, most of them Muslims, here are living on land that belongs to the Indian Railways. But residents say they have been living in the area for decades, and that the railways has no documents to support its claim.

In December, the state high court asked railway authorities to "evict unauthorised occupants" after giving them a week's notice. Residents started getting eviction notices from 1 January.

However, the Supreme Court on Thursday put a hold on the order, saying that "thousands cannot be uprooted overnight" and that a "workable solution" must be found.

As news of the order reached the residents, fear gave way to relief. Residents hugged and congratulated each other, happy for the temporary reprieve they had won.

But as the date of next hearing for the case on 7 February inches closer, the residents find themselves swinging between despair and hope. The BBC spoke to families whose future hangs in the balance.

For Tilka Devi Kashyap, 65, losing her home would mean imminent homelessness for her and her 14 family members.

Ms Kashyap arrived in the area in the mid-1970s and has invested her life's earnings to build her house.

A one-storey structure with tiny rooms, it is home to her sons, their wives and children.

Ms Kashyap and her family also depend on the area to make a living; they sell snacks on a cart outside their house.

The small business helps them make just enough money to see each day through. But talks about demolition has been affecting their business, she says.

"Customers have stopped frequenting the area," she told the BBC. "There are days when we are unable to save anything [after buying what's needed for the business] and have nothing to cook."

Ms Kashyap is among a small number of Hindus living in this predominantly Muslim neighbourhood. She says she was among those who voted for the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to power in the state in 2022.

"The government should think of the poor," she says, adding that it's the government's responsibility to provide alternate accommodation if their homes are demolished.

"We voted for the Congress [India's main opposition party] earlier. But we got nothing during both the BJP and Congress regimes."

Ms Kashyap says that she has been paying taxes and bills on her house for years and wonders why her home is suddenly being termed "illegal".

"The government shouldn't have let us settle here in the first place. Now that we have built everything, it wants to bring it [our house] down. Where will we go?" she asks.

Buying a house in another area isn't an option for Ms Kashyap. Her family has been poor, and their financial condition worsened after her husband had an accident five years ago.

The accident damaged his limbs and he has been unable to work since then. Costly medical bills of his treatment have hollowed out the family's meagre savings.

Ms Kashyap says she does not have the means to relocate or put up a legal fight to save her home, but she is determined to do what she can to prove that she and her home belong here.

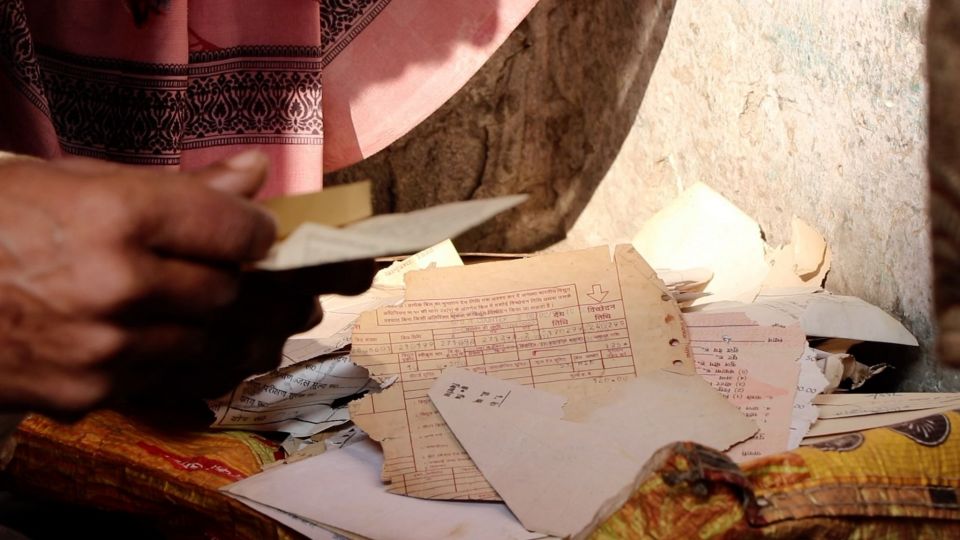

"I'm going to store all our bills more carefully," she says, rifling through a stack of crumpled bills that are torn in places.

"You never know when we might need them to prove our case before a government official."

'Our life and death depends on this case'

Zahida, who only uses one name, sits rolling chapatis (wheat flatbread) inside her dimly-lit tin-roofed shack.

She shares the space with her children, their spouses and her grandchildren. Conditions indoors are cramped and the interiors are worse for wear.

But to Zahida, who's in her 50s, and her family, the place is home.

"It may be in a bad condition, but at least we have a home. Where will we go if this is brought down?" she asks.

Zahida says that her ties to the house run deep; it's where she arrived as a newly-wed decades ago, raised her kids, and where her husband took his last breath.

The news that their house could be demolished has come as a blow to her. Like Ms Kashyap, the family is struggling financially.

A vegetable shop run by her eldest son helps them stay afloat. But the shop is set up in the same disputed locality, so losing their house would put an end to their business too, she says.

"We will end up on the streets. I think about this and cry day and night," Zahida says. "Our life and death depends on this case."