Will China help Russia cope with the fallout from economic sanctions?

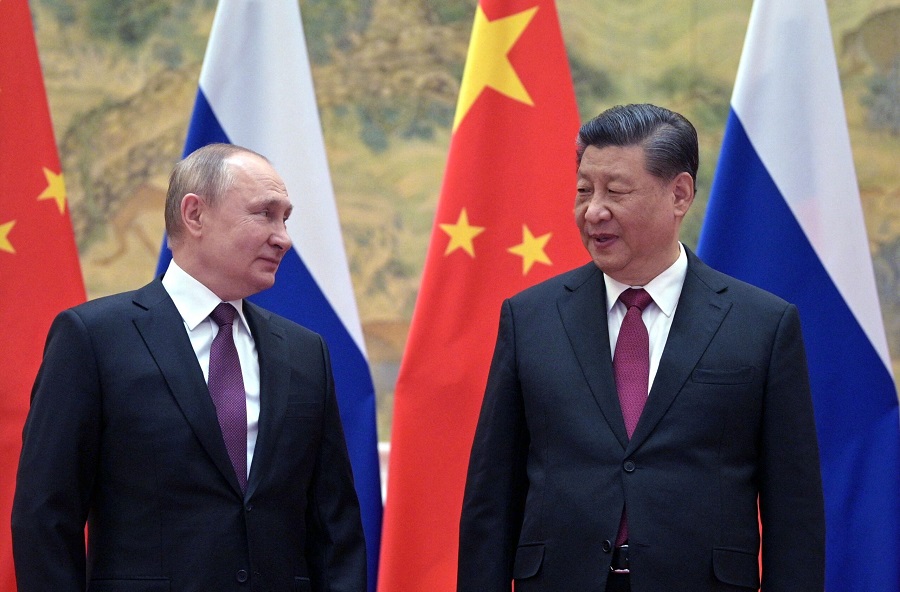

That has been the big question since Russia invaded Ukraine last week. The two nations have forged close ties in recent years, with Chinese leader Xi Jinping calling Russian President Vladimir Putin his "best and bosom friend" in 2019. During Putin's visit to Beijing last month, the two states proclaimed that their friendship has "no limits."

That was before Russia launched its war in Ukraine, and was hit with unprecedented sanctions from Western countries. Now, China's ability to help its neighbor is being sorely tested. Experts say Beijing's options are limited.

"China's leaders are walking a very difficult tightrope on Ukraine," said Craig Singleton, senior China fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, a DC-based think tank.

Beijing has not rushed to help Russia after its economy was slammed by sanctions from all over the world. On Wednesday, Guo Shuqing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, said that the country won't participate in sanctions, but he didn't offer any relief either.

Earlier this week, China's foreign minister spoke with his Ukrainian counterpart, and said that China was "deeply grieved to see the conflict" and that its "fundamental position on the Ukraine issue is open, transparent and consistent."

And the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a development bank backed by Beijing, said Thursday it was suspending all its activities in Russia as "the war in Ukraine unfolds."

"China's complicated messaging suggests that Beijing will continue to blame Washington and its allies for provoking Russia," Singleton said.

However, "such moves will fall far short of further antagonizing the United States on account of Beijing's desire to avoid a complete breakdown in US-China relations," he added.

Close but relatively small trading ties

Before Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Putin had deepened his country's ties with China significantly.

During his recent visit to China, the two countries signed 15 deals, including new contracts with Russian energy giants Gazprom and Rosneft. China also agreed to lift all import restrictions on Russian wheat and barley.

Last year, 16% of China's oil imports came from Russia, according to official statistics. This makes Russia the second biggest supplier to China after Saudi Arabia. About 5% of China's natural gas also came from Russia last year.

Russia, meanwhile, buys about 70% of its semiconductors from China, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics. It also imports computers, smart phones, and car components from China. Xiaomi, for example, is among the most popular smartphone brands in Russia.

China has also signed Russian banks onto its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), a clearing and settlement system seen as a potential alternative to SWIFT, the Belgium-based secure messaging service that connect hundreds of financial institutions around the world.

China and Russia share a strategic interest in challenging the West. But the invasion of Ukraine has put the friendship to the test.

Friendship test

"There is not yet any indication that China sees aiding Russia as worth violating Western sanctions," said Neil Thomas, a China analyst at Eurasia Group, adding that a "flagrant" defiance of those sanctions would come with a "heavy economic punishment" for Beijing as well.

"Beijing's much-touted lifting of import restrictions on Russian wheat was agreed before the invasion and does not indicate Chinese support," he said.

While Russia needs China for trade, Beijing has other priorities. The world's second largest economy is Russia's No. 1 trading partner, accounting for 16% of the value of its foreign trade, according to CNN Business' calculations based on 2020 figures from the World Trade Organization and Chinese customs data.

But for China, Russia matters a lot less: Trade between the two countries made up just 2% of China's total trade volume. The European Union and the United States have much larger shares.

Chinese banks and companies also fear secondary sanctions if they deal with Russian counterparts.

"Most Chinese banks cannot afford to lose access to US dollars and many Chinese industries cannot afford to lose access to US technology," said Thomas.

According to Singleton, these Chinese entities "could very quickly find themselves subject to increased Western scrutiny if they are perceived in any meaningful way as aiding Russian attempts to evade U.S.-led sanctions."

"Recognizing that China's economy and industrial output have been under enormous pressure in recent months, Chinese policymakers will likely attempt to strike a delicate balance between supporting Russia rhetorically but without antagonizing Western regulators," he added.

There have been reports this week that two of China's largest banks — ICBC and Bank of China — have restricted financing for purchases of Russian commodities, in fear of violating potential sanctions.

Reuters also reported Tuesday that China's coal imports from Russia have stalled because buyers couldn't secure funding from state banks worried about international sanctions.

ICBC and Bank of China did not respond to a request for comment from CNN Business.

Significant practical constraints

Even if China wants to support Russia in areas that are not subject to sanctions — such as energy — Beijing may face severe restrictions, experts said.

The "financial sanctions that have been imposed on Russia by the West put significant practical constraints on China's dealings with Russia even where they don't restrict them directly," said Mark Williams, chief Asian economist at Capital Economics, in a research note on Wednesday.

Some commentators have suggested that China's CIPS could be used as an alternative by Russia, now that seven Russian banks have been removed from SWIFT.

But CIPS is much smaller in size. It has only 75 direct participating banks, compared with more than 11,000 member institutions in SWIFT. About 300 Russian financial institutions are in SWIFT, while only two dozen Russian banks are connected to CIPS.

The yuan is also not freely convertible, and is used less frequently than other major currencies in international trade. It accounted for 3% of payments globally in January, compared with 40% in the dollar, according to SWIFT. Even China-Russia trade has been dominated by the dollar and euro.

"In practice, because CIPS is limited to payments in [yuan], it is only currently used for transactions with China. Banks elsewhere are unlikely to turn to CIPS as a SWIFT workaround while Russia is an international pariah," Williams said.

Neither can China replace the United States in providing key technologies for Russia's needs.

Last week, the Biden administration announced a series of measures to restrict technological exports or foreign goods built with US technology to Russia.

Russia imports mostly low-end computer chips from China, which are used in cars and home appliances. Both Russia and China rely on the United States for high-end chips needed for advanced weapons systems.

"China alone can't supply all of Russia's critical needs for the military," a senior US administration official said at a media briefing last week, according to Reuters. "China doesn't have any production of the most advanced technology nodes. So Russia and China are both reliant on other supplier countries and of course US technology to meet their needs."

That could lead Chinese tech companies — particularly larger ones — to exercise even more caution in potential deals with Russia.

"Some small Chinese firms that do not depend on US inputs may backfill some of Russia's demand for sanctioned US technology," said Thomas from Eurasia Group. "But big Chinese tech firms will be cautious to avoid the fate of Huawei, which the US government stunted by cutting its access to advanced semiconductors," he added.