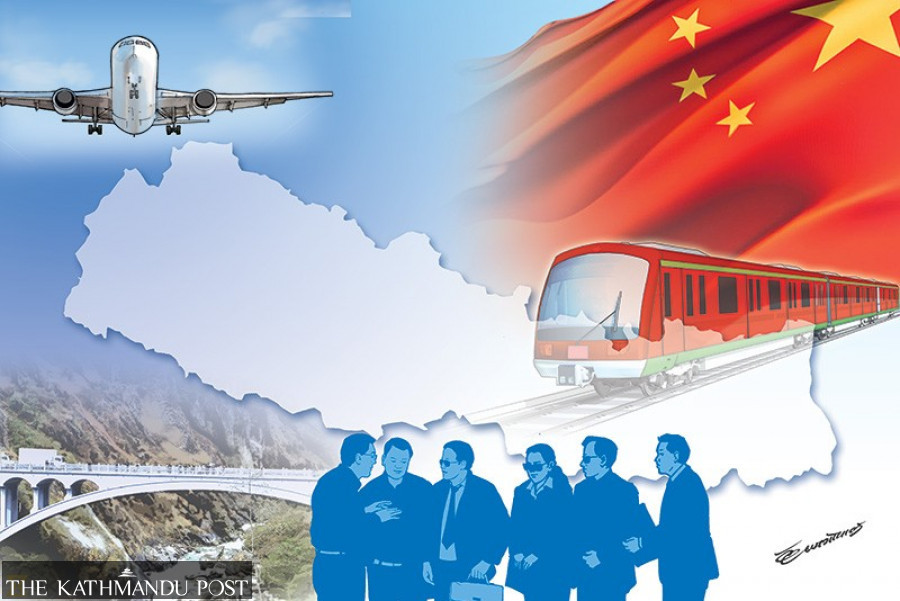

Last week marked the fifth anniversary of the signing of the Belt and Road Initiative between Nepal and China.

In February 2018, KP Sharma Oli became prime minister and visited China in the following June and read out 35 different projects Nepal would want to build under the BRI during his meeting with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang.

Nepal’s signing up to the BRI, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s flagship infrastructure initiative to connect China with Asia, Europe and Africa, was seen as a milestone. With Oli’s return to power—after signing a slew of agreements with Beijing during his earlier stint—with a strong mandate to lead a stable government, expectations were high over development of various projects under the BRI.

Five years down the line, the hopes seem to have faded though.

Since projects under the BRI are funded mostly with loans which Nepal did not prefer much, Kathmandu trimmed down the number of projects to nine, as per Chinese advice, said two government officials familiar with the matter.

According to them, the projects under the BRI are not even a priority.

There are multiple reasons the BRI has failed to gain momentum in Nepal.

“We had a slow start. It took time to select projects and then we trimmed down the number of selected projects from 35 to nine,” said Pradip Gyawali, who served as foreign minister in the Oli Cabinet. “As we were working on the project implementation plan and its framework, the pandemic hit, and the entire priority was shifted.”

According to Gyawali, now the Sher Bahadur Deuba government’s attitude towards the BRI is confusing.

Observers say there are political, ideological and practical reasons that have stymied BRI’s progress in Nepal.

Mrigendra Bahadur Karki, an associate professor at the Tribhuvan University, says Nepal’s preference to grant over loans, which the Deuba government made clear during Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit, also may not help projects under the BRI to take off.

“Nepal has a long experience of taking loans from multilateral agencies like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, among others, where interest rates are low and payback periods are long,” said Karki. “Nepal cannot afford commercial loans at higher interest rates.”

Multilateral agencies offer loans at a maximum of 1.5 percent, while commercial loan interest rates cross 2 percent.

One of the key components of the BRI is a cross-border railway which is also named the Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network.

During the visit by Chinese President Xi to Nepal in October 2019, it was agreed that “Nepal and China will take the Belt and Road Initiative as an important opportunity to deepen mutually beneficial cooperation in all fields in a comprehensive manner, jointly pursue common prosperity and dedicate themselves to maintaining peace, stability, and development in the region.”

According to a joint statement issued after the visit, the two sides agreed to intensify the implementation of the memorandum of understanding on cooperation under the BRI to enhance connectivity, encompassing such vital components as ports, roads, railways, aviation, and communications within the overarching framework of Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network with a view to significantly contributing to Nepal’s development agenda that includes graduating from LDC at an early date, becoming middle-income country by 2030 and realizing the SDGs by the same date.

The two sides also agreed to proactively cooperate on the feasibility study for the construction of tunnels along the road from Keyrung to Kathmandu. But due to the Covid pandemic, no progress was made on that front.

Again during the visit in March by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang, who is also the State Councilor, Nepal and China signed an agreement on a technical assistance scheme for the China-aided feasibility study of the cross-border railway.

In the first week of January, senior officials at the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and China Railway Administration held a meeting where the Chinese side had stated that it will take at least 42 months to complete the feasibility study of the railway project. A pre-feasibility study of the railway conducted in 2016 by China stated that complicated geological terrain and laborious engineering workload will become the most significant obstacles to building the cross-border railroad.

“China is still battling Covid-19 so work for conducting the feasibility study on Keyrung-Kathmandu railway has yet to begin in the field,” Aman Chitrakar, senior divisional engineer at the Department of Railways who is also a point person for the cross-border railway with China, told the Post. “Some of the Chinese cities are grappling with Covid so their work has been affected. That’s why they could not deploy the manpower. There are immense technical challenges given the topography. We need an in-depth study to ascertain various prospects before taking forward this project.”

Officials say they cannot say for sure when the railway project would take off, and as far as other projects under the BRI are concerned, Deuba’s communication to Wang that Nepal would prefer grants over loans has diminished the BRI prospects in Nepal.

During a virtual media briefing in April, Chinese ambassador to Nepal Hou Yanqi also said that BRI is not a grant assistance and is based on cooperation and cooperative modality that includes grant and commercial cooperation.

A Finance Ministry official said that due to a high interest rate, the Nepali side gave up the idea of taking commercial loans from Chinese banks and financial institutions.

Hou, however, said that the BRI cooperation between China and Nepal “has not got bogged down.”

“On the contrary, it has become a road of hope that bolsters resilience and boosts confidence,” she said. “I would like to point out that the BRI has never been a geopolitical strategy, but a road of development.”

According to former Nepali envoy to China, Rajeshwar Acharya, the BRI is in limbo in Nepal also because of frequent changes in the government in Kathmandu.

“And a lack of proper diplomacy is another reason,” Acharya told the Post.

Hou, during the press briefing, had also pointed out how frequent government changes affect cooperation efforts.

“Government changes are natural in democratic countries and it is their internal matter. However, a change in policies with the change in the government is a cause for concern,” said Hou. “This affects the investors mainly in large projects. Construction of hydropower projects or other industries takes time where the investors make long-term planning and investment. However, a frequent change in policies affects them.”

According to Acharya, Nepal’s diplomacy has not been consistent due to a lack of study, consultation with thematic experts and politicians’ reluctance to incorporate inputs from think tanks while formulating the country’s foreign policy.

“If BRI projects can be implemented through loans only, then we should convince the Chinese that we cannot afford high-interest loans. Nepal should sit down and talk with China to find a new funding modality,” said Acharya. “It may take some time but negotiations are the only way to a better deal.”

Those government officials who are working to execute projects under the BRI said that before the next general elections, it is unlikely that Nepal and China would resume talks.

Former foreign minister Gyawali agrees.

“Not all loans are bad. We also should carefully study the terms and conditions of such loans. And, we should also give final touches to the implementation plan for the projects which we had initiated under the BRI,” said Gyawali. “The Deuba government is giving very mixed and confusing signals regarding finalising the text of the implementation plan, and flatly told the Chinese that Nepal prefers grants, not loans. So I think given the current situation, BRI negotiations will be delayed.”

Nepal is in its election year now, with local level polls concluded just last week. Two more elections—federal and provincial—are due later this year.

Observers say geopolitical factors have also come into play now which may affect BRI implementation in Nepal. In the recent past, there have been rapid developments in the cooperation sector, with the ratification of the $500 million Millennium Challenge Corporation grant by Nepal, and India’s renewed interest in investing in Nepal, especially in the hydropower sector.

Both Washington and New Delhi have since long taken a dim view of the BRI, with US officials even obliquely warning Kathmandu officials of a possible debt trap.

Karki, the assistant professor, says Beijing is unlikely to revisit its BRI policy only for Nepal if Kathmandu continues to insist on grants.

“Definitely the Nepal-China cross border railway was proposed by China with the Indian market in mind, because Nepal with a country of just 30 million people cannot cater to the objectives of the BRI. But India has strong reservations about the BRI and termed it a strategic, political and economic tool to expand the Chinese clout,” said Karki. “Now that the Deuba government too has conveyed that it is not interested in loans. So I don’t see any possibility of BRI projects moving ahead at least until the general elections.”